Gloriously remote, St. Kilda is an archipelago 50 miles off the Isle of Harris, and are the most westerly islands of the Outer Hebrides. Although far from the nearest land, St Kilda is visible from as far as the summit ridges of the Skye Cuillin, some 80 miles distant. Although the four islands are uninhabited by humans, thousands of seas birds call these craggy cliffs home, clinging to the sheer faces as if by magic. Not only is St. Kilda home to the UK’s largest colony of Atlantic Puffin (almost 1 million), but also the world largest colony Gannets nests on Boreray island and its sea stacks. The islands also home decedents of the world’s original Soay sheep as well as having a breed of eponymous named mice. The extremely rare St. Kilda wren unsurprisingly hails from St. Kilda.

Currently, the only year-round residents are military personnel; a variety of conservation workers, volunteers and scientists spend time there in the summer months. The National Trust for Scotland owns the entire archipelago. It became one of Scotland's six World Heritage Sites in 1986 and is one of the few in the world to hold mixed status for both its natural and cultural qualities. Parties of volunteers work on the islands in the summer to restore the many ruined buildings that the native St Kildans left behind. They share the island with a small military base established in 1957.

The climate is oceanic with high rainfall( 55 in), and high humidity. Temperatures are generally cool, averaging 5 °C in January and 12 °C in July. The prevailing winds are especially strong in winter, Gale-force winds occur less than 2 per cent of the time in any one year, but gusts of 115 miles per hour and more occur regularly on the high tops, The tidal range is 10ft , and ocean swells of 15 ft frequently occur, which can make landings difficult or impossible at any time of year. The oceanic location protects the islands from snow, which lies for only about a dozen days per year.

|

|

Puffins |

Soay Ram |

While endemic animal species is rife on the island, St. Kilda has not been peopled since 1930 after the last inhabitants voted that human life was unsustainable. However, permanent habitation had been possible in the Medieval Ages, and a vast National Trust for Scotland project to restore the dwellings is currently being undertaken. Today, the only humans living on the islands are passionate history, science and conservation scholars. One of the caretakers even acts as shopkeeper and postmaster for any visitors who might like to send a postcard home from St. Kilda. It should be noted that St. Kilda is the UKs only (and just one of 39 in the world) dual World Heritage status from UNESCO in recognition of its Natural Heritage and cultural significance

Hirta

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Gleann Mor |

Dun Island |

The largest island is Hirta, whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom. Three other islands (Dùn, Soay and Boreray) were also used for grazing and seabird hunting.

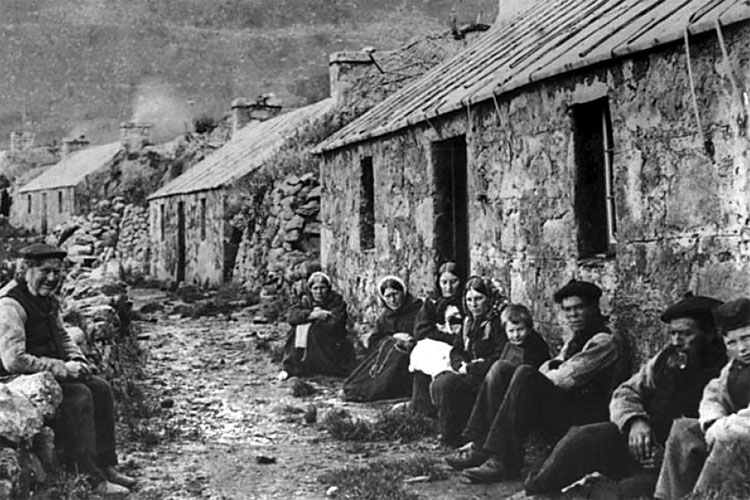

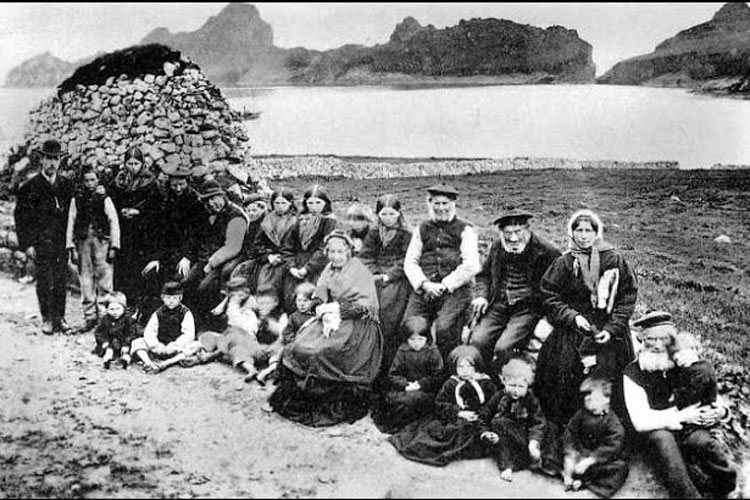

The islands' human heritage includes numerous unique architectural features from the historic and prehistoric periods, although the earliest written records of island life date from the Late Middle Ages. The medieval village on Hirta was rebuilt in the 19th century, but illnesses brought by increased external contacts through tourism and the upheaval of the First World War contributed to the island's evacuation in 1930. Permanent habitation on the islands possibly extends back two millennia, the population probably never exceeding 180 (and certainly no more than 100 after 1851). In modern times, St Kilda's only settlement was at Village Bay on Hirta. There are also ancient remains of buildings at Gleann Mòr on the north coast of Hirta

The entire remaining population was evacuated from Hirta, the only inhabited island, in 1930. The islands house a unique form of stone structure known as cleitean. A cleit is a stone storage hut or bothy; while many still exist, they are slowly falling into disrepair. There are known to be 1,260 cleitean on Hirta and a further 170 on the other group islands.

At 1,700 acres in extent, Hirta comprises more than 78% of the land area of the archipelago. Next in size are Soay (English: "sheep island") at 240 acres and Boreray ('the fortified isle'), with 190 acres. Soay is 0.25 mile north-west of Hirta, Boreray 4 miles to the north-east. Smaller islets and stacks in the group include Stac an Armin ('warrior's stack'), Stac Lee ('grey stack') and Stac Levenish ('stream' or 'torrent'). The island of Dùn ('fort'), which protects Village Bay from the prevailing southwesterly winds, was at one time joined to Hirta by a natural arch. One theory is the arch was struck by a galleon fleeing the defeat of the Spanish Armada, but other sources suggest the arch was swept away by one of the many fierce winter storms that annually batter the islands. The highest point in the archipelago, Conachair ('the beacon') at 1,410 ft, is on Hirta, immediately north of the village, and is faced with vertical rock cliffs up to 1,401 ft high, which constitute the highest sea cliffs in the UK. The extraordinary Stac an Armin reaches 643 ft, and Stac Lee,564 ft, making them the highest sea stacks in Britain.

Soay

|

|

Boreray

Boreray also contains the remains of earlier habitations,

|

|

|

|

History

1202. The first written record of St Kilda is from an Icelandic cleric who wrote of taking shelter on "the islands that are called Hirtir". Early reports mentioned finds of brooches, an iron sword and Danish coins. The enduring Norse place names indicate a sustained Viking presence on Hirta, but the visible evidence has been lost. In the late 14th century John of Fordun referred to it as 'the isle of Irte (insula de Irte), which is agreed to be under the Circius and on the margins of the world'.

1549. The islands were historically part of the domain of the MacLeods of Harris, whose steward was responsible for the collection of rents in kind and other duties. The first detailed report of a visit to the islands dates from 1549, when Donald Munro suggested that: "The inhabitants thereof ar simple poor people, scarce learnit in aney religion, but M’Cloyd of Herray, his stewart, or he quhom he deputs in sic office, sailes anes in the zear ther at midsummer, with some chaplaine to baptize bairnes ther." Despite the chaplain's best efforts, the islanders' isolation and dependence on the bounty of the natural world meant their philosophy bore as much relationship to Druidism as it did to Christianity.

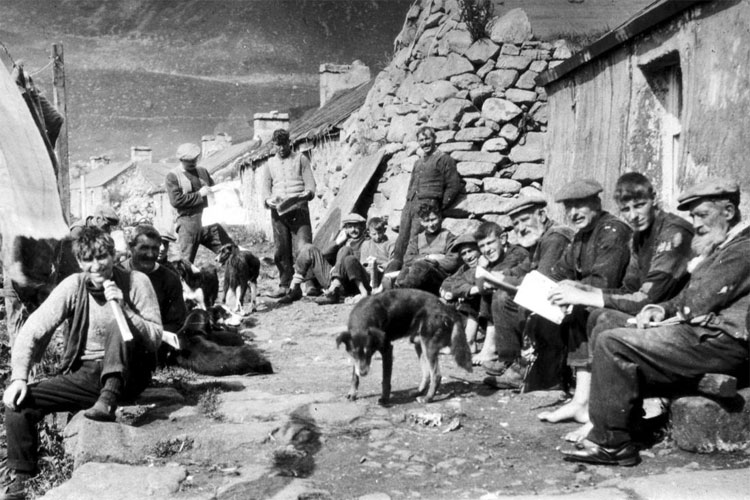

1697. At the time of Martin's visit the population was 180, and the steward travelled with a "company" of up to 60 persons to which he "elected the most 'meagre' among his friends in the neighbouring islands, to that number and took them periodically to St Kilda to enjoy the nourishing and plentiful, if primitive, fare of the island, and so be restored to their wonted health and strength. A significant feature of St Kildan life was the diet. The islanders kept sheep and a few cattle and were able to grow a limited amount of food crops, such as barley and potatoes, on the better-drained land in Village Bay; in many ways the islands can be seen as a large mixed farm. Samuel Johnson reported that in the 18th-century sheep's milk was made "into small cheeses" by the St Kildans.] They generally eschewed fishing because of the heavy seas and unpredictable weather. The mainstay of their food supplies was the profusion of island birds, especially gannet and fulmar. These they harvested as eggs and young birds and ate both fresh and cured. Adult puffins were also caught by the use of fowling rods.

1705. A missionary called Alexander Buchan went to St Kilda , but despite his extended stay, the idea of organised religion did not take hold.

1727, the loss of life from smallpox and cholera contacted from visiting ships was so high that too few residents remained to man the boats, and new families were brought in from Harris to replace them.

1758, the population had risen to 88 and reached just under 100 by the end of the century. This figure remained fairly constant from the 18th century until 1851

1764 census described a daily consumption for each of the 90 inhabitants at the same of "36 wild fouls eggs and 18 fouls" (i.e. seabirds). And the same year Macauley reported the existence of five druidic altars, including a large circle of stones fixed perpendicularly in the ground near the Stallir House on Boreray.

1822. Rev. John MacDonald, the "Apostle of the North", arrived and set about his mission with zeal, preaching 13 lengthy sermons during his first 11 days. He returned regularly and raised funds on behalf of the St Kildans, although privately he was appalled by their lack of religious knowledge. The islanders took to him with enthusiasm and wept when he left for the last time eight years later.

1830 Rev MacDonald's successor arrived . He was Rev. Neil Mackenzie, a resident Church of Scotland minister who significantly improved the conditions of the inhabitants. He reorganised island agriculture, was instrumental in the rebuilding of the village and supervised the building of a new church and manse. With help from the Gaelic School Society, MacKenzie and his wife introduced formal education to Hirta, beginning a daily school to teach reading, writing and arithmetic and a Sunday school for religious education .Mackenzie left in 1844,

1851. 36 islanders emigrated to Australia on board the Priscilla, a loss from which the island never fully recovered. The emigration was in part a response to the laird's closure of the church and manse for several years during the Disruption that created the Free Church of Scotland.

1865. A new minister arrived - Rev. John Mackay . Despite their fondness for Rev Mackenzie, who stayed in the Church of Scotland, the St Kildans "came out" in favour of the new Free Church during the Disruption. Mackay, the new Free Church minister, placed an uncommon emphasis on religious observance. He introduced a routine of three two-to-three-hour services on Sunday at which attendance was effectively compulsory. One visitor noted in 1875 that: "The Sabbath was a day of intolerable gloom. At the clink of the bell, the whole flock hurry to Church with sorrowful looks and eyes bent upon the ground. It is considered sinful to look to the right or to the left." Time spent in religious gatherings significantly interfered with the practical routines of the island. Old ladies and children who made noise in church were lectured at length and warned of dire punishments in the afterworld. During a period of food shortages on the island, a relief vessel arrived on a Saturday, but the minister said that the islanders had to spend the day preparing for church on the Sabbath, and it was Monday before supplies were landed. Children were forbidden to play games and required to carry a Bible wherever they went. Mackay remained minister on St Kilda for 24 years

|

|

|

|

|

|

1899 Norman Heathcote visited the islands and wrote a book about his experiences. During the 19th century, steamers had begun to visit Hirta, enabling the islanders to earn money from the sale of tweeds and birds' eggs; but it was at the expense of their self-esteem as the tourists regarded them as curiosities. It is also clear that the St Kildans were not so naïve as they sometimes appeared. "For example, when they boarded a yacht they would pretend they thought all the polished brass was gold, and that the owner must be enormously wealthy". The boats brought other previously unknown diseases, especially tetanus infantum, which resulted in infant mortality rates as high as 80 per cent during the late 19th century.

By the early 20th century, formal schooling had become a feature of the islands, and in 1906 the church was extended to make a schoolhouse. The children all now learned English, as well as their native Scottish Gaelic. Improved midwifery skills, reduced the problems of childhood tetanus. From the 1880s, trawlers fishing the North Atlantic made regular visits, bringing additional trade. Talk of an evacuation occurred in 1875, during MacKay's time as minister, but despite occasional food shortages and a flu epidemic in 1913, the population was stable at between 75 and 80. There was no obvious sign that within a few years the millennia-old occupation of the island was to end.

Early in the First World War, the Royal Navy manned the signal station on Hirta, and daily communications with the mainland were established. In a belated response, the German submarine SM U-90 arrived in Village Bay on the morning of 15 May 1918 and, after issuing a warning, started shelling the island. Seventy-four shells were fired, and the wireless station was destroyed. The manse, church, and jetty storehouse were damaged, but there was no loss of life.One eyewitness recalled: "It wasn't what you would call a bad submarine because it could have blowed every house down because they were all in a row there. He only wanted Admiralty property. One lamb was killed... all the cattle ran from one side of the island to the other when they heard the shots." As a result of this attack, a 4-inch Mark III QF gun was erected on a promontory overlooking Village Bay, but it never saw action against the enemy. Of greater long-term significance to the islanders were the introduction of regular contact with the outside world and the slow development of a money-based economy. This made life easier for the St Kildans but also made them less self-reliant. Both were factors in the evacuation of the island a little more than a decade later.

The islands' inhabitants had existed for centuries in relative isolation until tourism and the presence of the military during the First World War led the islanders to seek alternatives to privations they routinely suffered. The changes on the island by visitors in the nineteenth century disconnected the islanders from their traditional way of life, which had allowed their forebears to survive in this unique environment. Despite the construction of a small jetty in 1902, the islands remained at the weather's mercy. After the War, most of the young men left the island, and the population fell from 73 in 1920 to 37 in 1928. After the death of four men from influenza in 1926, there was a succession of crop failures in the 1920s. University of Aberdeen investigations into the soil where crops had been grown has shown that there had been contamination of lead and other pollutants, caused by the use of seabird carcasses and peat ash in the manure used on the fields. Contamination occurred over a lengthy period of time, as manuring practices became more intensive, and may have been a factor in the evacuation. The last straw came in January 1930 when a young woman, Mary Gillies, fell ill and was taken to the mainland for treatment, where she died in hospital. For many years it was assumed that her death was caused by appendicitis; but her son, Norman John Gillies, discovered in 1991 that she had died of pneumonia after giving birth to a daughter, who also died.

One of the main initiators of the evacuation was nurse Williamina Barclay, who had been stationed at St Kilda in 1928. She reported her observations on the conditions on the island to the Scottish Department of Health. She convinced many of the islanders to evacuate and helped the islanders draw up an official petition to request assistance with the evacuation and resettlement on the mainland. Barclay was appointed the government's representative on St Kilda in June 1930 and was made responsible for the planning of the evacuation and the resettlement of the St Kildans on the mainland. All the cattle and sheep were taken off the island two days before the evacuation for sale on the mainland. However, all the island's working dogs were drowned in the bay because they could not be taken. On 29 August 1930, a ship called Harebell took the remaining 36 inhabitants to Morvern on the Scottish mainland, a decision they all took collectively. The morning of the evacuation was a perfect day. The sky was hopelessly blue and the sight of Hirta, green and pleasant as the island of so many careless dreams, made parting all the more difficult. Observing tradition the islanders left an open Bible and a small pile of oats in each house, locked all the doors and at 7 am boarded the Harebell. The last of the native St Kildans, Rachel Johnson, died in April 2016 at the age of 93, having been evacuated at the age of 8. In 1931, the islands' laird, Sir Reginald MacLeod of MacLeod, sold them to Lord Dumfries, who later became the 5th Marquess of Bute. For the next 26 years, they saw few people, save for the occasional summer visitors or a returning St Kildan family.

The islands saw no military activity during the Second World War, remaining uninhabited, but three aircraft crash sites remain from that period. A Beaufighter LX798 based at Port Ellen on Islay crashed into Conachair within 300 ft of the summit on the night of 3–4 June 1943. A year later, just before midnight on 7 June 1944, the day after D-Day, a Sunderland flying boat ML858 was wrecked at the head of Gleann Mòr. A small plaque in the church is dedicated to those who died in this accident. A Wellington bomber crashed on the south coast of Soay in 1942 or 1943. Not until 1978 was any formal attempt made to investigate the wreck, and its identity has not been absolutely determined. Amongst the wreckage, a Royal Canadian Air Force cap badge was discovered, which suggests it may have been HX448 of 7 OTU which went missing on a navigation exercise on 28 September 1942. Alternatively, it has been suggested that the Wellington is LA995 of 303 FTU which was lost on 23 February 1943.

In 1955, the British government decided to incorporate St Kilda into a missile tracking range based in Benbecula, where test firings and flights are carried out. Thus in 1957, St Kilda became permanently inhabited once again. A variety of military buildings and masts have since been erected, including a canteen, the Puff Inn. The Ministry of Defence (MoD) leases St Kilda from the National Trust for Scotland for a nominal fee. The main island of Hirta is still occupied year-round by a small number of civilians employed by defence contractor QinetiQ working in the military base (Deep Sea Range) on a monthly rotation. In 2009 the MoD announced that it was considering closing down its missile testing ranges in the Western Isles, potentially leaving the Hirta base unmanned. In 2015 the base had to be temporarily evacuated due to adverse weather conditions. By 2018, plans to rebuild the MoD base were underway. With no permanent population, the island population can vary between 20 and 70. These inhabitants include: MoD employees, National Trust for Scotland employees, and several scientists working on a Soay sheep research project.