|

|

|

|

The Battle of Flores was a naval engagement of the Anglo-Spanish War of 1585 fought off the Island of Flores between an English fleet of 22 ships under Lord Thomas Howard and a Spanish fleet of 55 ships under Alonso de Bazán.

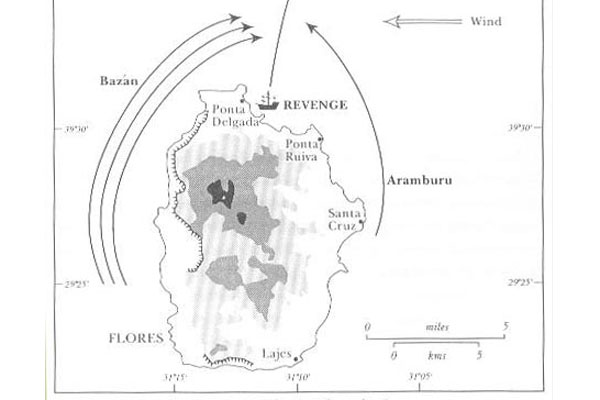

Sent to the Azores to capture the annual Spanish treasure convoy, when a stronger Spanish fleet appeared off Flores, Howard ordered his ships to flee to the north,[5] saving all of them except the galleon Revenge commanded by Admiral Sir Richard Grenville. After transferring his ill crewmen onshore back to his ship, he led the Revenge in a rearguard action against 55 Spanish ships, allowing the English fleet to retire to safety. The crew of the Revenge sank and damaged several Spanish ships during a day-and-night running battle. The Revenge was boarded many times by different Spanish ships, and repelled each attack successfully. When Admiral Sir Richard Grenville was badly wounded, his surviving crew surrendered. Alfred, Lord Tennyson, wrote a poem about the battle, entitled The Revenge: a Ballad of the Fleet.

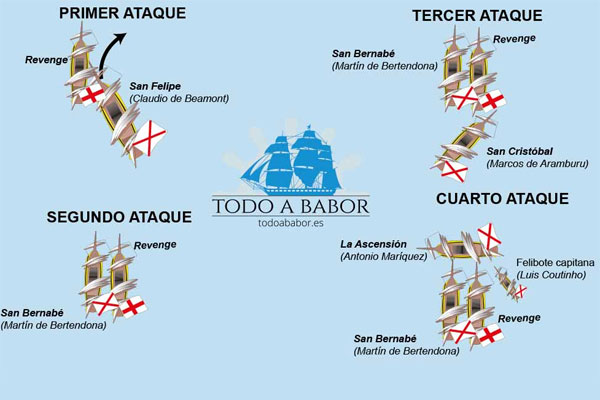

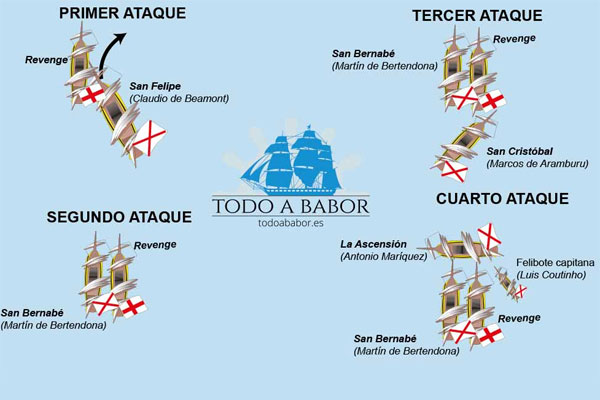

Bazán tried to surprise the English fleet at anchor, but Sancho Pardo's vice-flagship lost their bowsprit, forcing the attack to be delayed. It was not until 5 pm that Bazán's ships bore down the channel which separated Flores and Corvo islands. Howard, alerted to the arrival of the Spanish, managed to slip away to sea. An exchange of fire took place between both fleets before they became separated. Grenville, however, preferred to fight and went straight through the Spaniards, who were approaching from the eastward. Meanwhile, Defiance, Howard's flagship, received heavy gunfire from Aramburu's San Cristóbal before withdrawing from the battle. Revenge was left behind and directly engaged by Claudio de Viamonte's San Felipe. Viamonte boarded the English galleon, suffering the misfortune of the grappling hook parting after having only passed 10 men aboard her.

Shortly after Martín de Bertendona's San Bernabé did the same, this time successfully, and managed to rescue seven survivors of San Felipe's boarding party. San Bernabé's grappling was decisive to the fate of Revenge, because the English warship lost the advantage of her long-range naval guns. Conversely, the heavy musketry fire of the Spanish infantry forced the English gunners to abandon their post in order to repulse the attack. At dusk, having dispersed the bulk of the English fleet, San Cristobal rammed Revenge underneath its aftcastle, putting on board of the English ship a second boarding party which captured her colours. The Spanish soldiers got as far forward as the mainmast before being forced to retreat, due to heavy musketry fire from the aftcastle.

San Cristóbal's bow had been shattered by the ramming, and she had to ask for reinforcements. Antonio Manrique's Asunción and Luis Coutinho's flyboat La Serena attacked at the same time, increasing the number of ships beating the Revenge to five, which was still grappled by the galleons San Bernabé and the damaged San Cristóbal. Grenville held them back with cannon and musket fire until, being himself badly injured and Revenge severely damaged, completely dis-masted and with 150 men killed or unable to fight, surrendered. During the night Manrique's and Coutinho's ships sank after they collided with each other.

Despite the damage Grenville had inflicted, the Spanish treated Revenge's survivors honourably. Grenville, who had been taken aboard Bazán's flagship, died two days later. The Spanish Treasure Fleet rendezvoused with Bazán soon afterward, and the combined fleet sailed to Spain. They were overtaken by a week-long storm during which Revenge and 15 Spanish warships and merchant vessels were lost. Revenge sank with her mixed prize-crew of 70 Spaniards and English prisoners near the island of Terceira. The battle, however, marked the resurgence of Spanish naval power and proved that the English chances of catching and defeating a well-defended treasure fleet were remote. It also hinted at what might have happened in Gravelines in 1588 if Medina Sidonia had succeeded in luring the English ships within grappling range of the Armada, and if the cannonballs had actually fitted the Spanish cannon (they had been manufactured in different areas of the Spanish Habsburg Empire, and so were not all designed in the same way, shape, or size).

At Flores in the Azores Sir Richard Grenville lay,

And a pinnace, like a flutter'd bird, came flying from far away.

‘Spanish ships of war at sea! We have sighted fifty three!'

Then sware Lord Thomas Howard: ‘'Fore God I am no coward;

But I cannot meet them here, for my ships are out of gear,

And half my men are sick. I must fly, but follow quick.

We are six ships of the line; can we fight with fifty three?'

Then spake Sir Richard Grenville: ‘I know you are no coward;

You fly them for a moment to fight with them again.

But I've ninety men and more that are lying sick ashore.

I should count myself the coward if I left them, my Lord Howard,

To those Inquisition dogs and the devildoms of Spain.'

So Lord Howard past away with five ships of war that day,

Till he melted like a cloud in the silent summer heaven;

But Sir Richard bore in hand all his sick men from the land

Very carefully and slow,

Men of Bideford in Devon,

And we laid them on the ballast down below;

For we brought them all aboard,

And they blest him in their pain, that they were not left to Spain,

To the thumbscrew and the stake, for the glory of the Lord.

He had only a hundred seamen to work the ship and to fight,

And he sail'd away from Flores till the Spaniard came in sight,

With his huge sea-castles heaving upon the weather bow.

‘Shall we fight or shall we fly?

Good Sir Richard, tell us now,

For to fight is but to die!

There'll be little of us left by the time this sun be set.'

And Sir Richard said again: ‘We be all good English men,

Let us bang these dogs of Seville, the children of the devil,

For I never turned my back on Don or devil yet.'

Sir Richard spoke and he laugh'd, and we roar'd a hurrah, and so

The little 'Revenge' ran on, sheer into the heart of the foe,

With her hundred fighters on deck, and her ninety sick below;

For half of their fleet to the right and half to the left were seen,

And the little 'Revenge' ran on thro' the long sea-lane between.

Thousands of their soldiers look'd down from their decks and laugh'd,

Thousands of their seamen made mock at the mad little craft

Running on and on, till delay'd

By their mountain-like 'San Philip' that, of fifteen hundred tons,

And up-shadowing high above us with her yawning tiers of guns,

Took the breath from our sails, and we stay'd.

And while now the great 'San Philip' hung above us like a cloud

Whence the thunderbolt will fall

Long and loud,

Four galleons drew away

From the Spanish fleet that day,

And two upon the larboard and two upon the starboard lay,

And the battle-thunder broke from them all.

But anon the great 'San Philip,' she bethought herself and went

Having that within her womb that had left her ill content;

And the rest they came aboard us, and they fought us hand to hand,

For a dozen times they came with their pikes and their musketeers,

And a dozen time we shook ‘em off as a dog that shakes its ears

When he leaps from the water to the land.

And the sun went down, and the stars came out far over the summer seas,

But never a moment ceased the fight of the one and the fifty-three.

Ship after ship, the whole night long, their high-built galleons came,

Ship after ship, the whole night long, with her battle-thunder and flame;

Ship after ship, the whole night long, drew back with her dead and her shame.

For some were sunk and many were shatter'd, and so could fight us no more--

God of battles, was ever a battle like this in the world before?

For he said ‘Fight on! Fight on!'

Tho' his vessel was all but a wreck;

And it chanced that, when half of the short summer night was gone,

With a grisly wound to be dressed he had left the deck,

But a bullet struck him that was dressing it suddenly dead,

And himself he was wounded again in the side and the head,

And he said ‘Fight on! Fight on!'

And the night went down, and the sun smiled out from over the summer sea,

And the Spanish fleet with broken sides lay around us all in a ring;

But they dared not touch us again, for they fear'd that we still could sting,

So they watch'd what the end would be.

And we had not fought them in vain,

But in perilous plight were we,

Seeing forty of our poor hundred were slain,

And half of the rest of us maim'd for life

In the crash of the cannonades and the desperate strife;

And the sick men down in the hold were most of them stark and cold,

And the pikes were all broken or bent, and the powder was all of it spent;

And the masts and the rigging were lying over the side;

But Sir Richard cried in his English pride,

‘We have fought such a fight for a day and a night

As may never be fought again!

We have won great glory. my men!

And a day less or more

At sea or ashore,

We die--does it matter when?

Sink me the ship, Master Gunner--sink her, split her in twain!

Fall into the hands of God, not into the hands of Spain!'

And the gunner said ‘Ay, ay', but the seamen made reply:

‘We have children, we have wives,

And the Lord hath spared our lives.

We will make the Spaniard promise, if we yield, to let us go;

We shall live to fight again and to strike another blow.'

And the lion there lay dying, and they yielded to the foe.

And the stately Spanish men to their flagship bore him then,

Where they laid him by the mast, old Sir Richard caught at last,

And they praised him to his face with their courtly foreign grace.

But he rose upon their decks and he cried:

‘I have fought for Queen and Faith like a valiant man and true;

I have only done my duty as a man is bound to do:

With a joyful spirit I Sir Richard Grenville die!'

And he fell upon their decks and he died.

And they stared at the dead that had been so valiant and true,

And had holden the power and the glory of Spain so cheap

That he dared her with one little ship and his English few;

Was he devil or man? He was devil for aught they knew,

But they sank his body with honour down into the deep,

And they mann'd the 'Revenge' with a swarthier alien crew,

And away she sail'd with her loss and long'd for her own;

When a wind from the lands they had ruin'd awoke from sleep,

And the water began to heave and the weather to moan,

And or ever that evening ended a great gale blew,

And a wave like a wave that is raised by an earthquake grew,

Till it smote on their hulls and their sails and their masts and their flags,

And the whole sea plunged and fell on the shot-shatter'd navy of Spain,

And the little 'Revenge' herself went down by the island crags

To be lost evermore in the main.